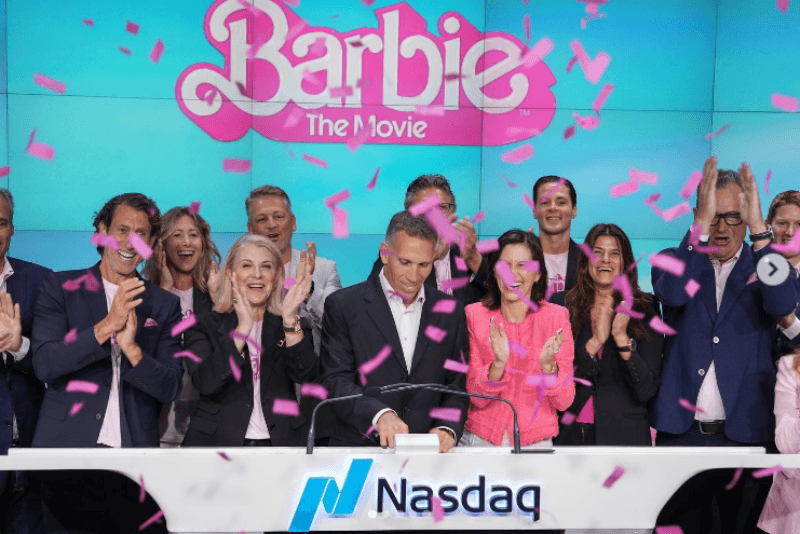

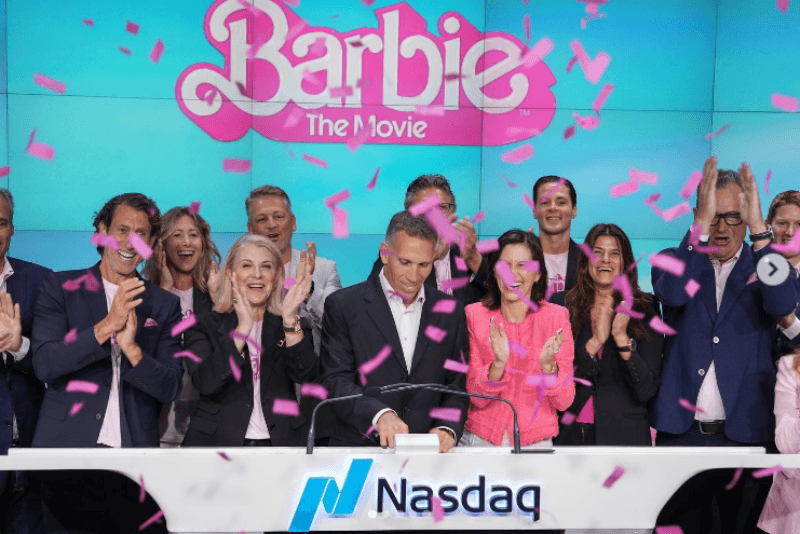

The scene of the president of Mattel opening the New York Stock Exchange under a shower of pink confetti is emblematic in demonstrating what the recently released Barbie movie is about: a significant piece of reactionary propaganda, not only for the company that produces the doll, which has seen an 18% increase (1 billion dollars) in the value of its shares since the movie’s release but also for a whole set of decaying bourgeois ideas regarding the issue of women.

Seeking to make their worldview reach the bourgeoisie as far as possible, they spared no expense on marketing. Millions of dollars have been spent from the announcement of the premiere until now to make it increasingly difficult to walk through cities without encountering a promotional piece of the film. Billboards, social media, television, and even the clothes people wear on a daily basis have become a major showcase for promoting the work, an investment that will yield even greater returns.

Another important aspect of the movie’s promotion is the widespread praise it has been receiving from bourgeois feminists. They have been treating the film as the most modern manifesto for combating patriarchy. People who, until recently, rejected Barbie as just another tool for imposing oppressive standards of femininity now dress in pink and advocate for the doll as the ultimate symbol of female “empowerment.”

While discussing the class nature of the issue, bourgeois and petit-bourgeois feminism fail to provide a comprehensive analysis, remaining limited to what the work itself has to say. According to this logic, it would be sufficient for the film to declare itself as a progressive piece combating patriarchy to actually be one. However, as class struggle manifests in culture, there are obviously interests behind producing films like this, and therefore, to determine the character of a work, we must ask ourselves which class it serves and the worldview of which class it promotes.

If we don’t let ourselves be swept along like a herd behind the movie’s advertising and promotion and instead start from the perspective of the working classes, we soon realize that in the case of the new Barbie movie, it’s the worldview of the declining bourgeoisie that is being disseminated, and not that of the exploited workers increasingly subjected to more precarious working and living conditions.

The plot of the movie aims to depict the journey taken by a Barbie, from her always perfect life in the world of Barbies, Barbie Land, to the real world, where she encounters a series of contradictions that are new to her and will eventually manifest in her fantasy world.

From the beginning, the film’s producers attempt to use Barbie Land as a sort of inverted representation of their vision of society. Thus, by analyzing what this fictional land is and how it functions, we can get an idea of their conception of our own reality. That is, the view that society is divided by gender rather than class. In Barbie Land, there is no class division; the only social distinction that can be found is between women, the Barbies, who hold positions of power, and men, the Kens, who play a secondary role, essentially existing in relation to women’s existence. It is precisely in this inversion of the social position of men and women that the irony of the film supposedly resides, while still emphasizing the need for a man to reaffirm the value of women.

This idea of dividing society based on gender rather than class is typical of bourgeois feminism and its post-modern derivations, which express the reactionary notion of opposition between men and women without taking into account the class to which they belong. They place exploited working women and exploitative female entrepreneurs side by side in an attempt to reconcile antagonistic classes based on gender. This conception is nothing more than an ideological weapon of the bourgeoisie within the women’s movement, seeking to divide men and women so that they do not unite to fight against the system of oppression and exploitation by capital. But in the world of Barbie, there are no classes; it’s a kind of matriarchy where all women are professionally successful, whether they are employers or workers. With men, there are differences, but their social function is to worship them. It’s a kind of perfect feminist world that borders on a ridiculous fantasy.

At a certain point in the movie, Barbie decides to go to the “real” world, and Ken follows her. Surprisingly, the real world is California, as traditionally represented in all American clichéd movies, and not the deep United States with anti-racist protests and homelessness after the 2008 crisis. In this “real” world, they discover sexism and patriarchy, and, fascinated by the discovery of a world where men are in charge, the Kens decide to establish patriarchy in Barbie Land, with the support of the Barbies themselves, who embrace the new system with open arms. Once again, the movie’s narrative reflects the perspective of bourgeois feminism on what patriarchy is and how it originated in our society. It portrays women’s oppression as a result of men’s conscious desire to subjugate women, rather than a direct consequence of the economic relationships stemming from the emergence of private property and class society.

The solution that the movie attempts to provide for this new situation of women’s oppression is even more idealistic and reactionary; the solution to oppression is for women to become aware of their own situation, and once all women are socially conscious, the only thing left to do is to fight within the framework of the Old State to overthrow reactionary laws and establish new progressive laws, thus transforming society and making women’s oppression a thing of the past. This idea reverses reality, portraying it as a reflection of the laws rather than the laws as a legal reflection of the concrete way a society is organized. The Barbie Revolution is a new constituent assembly in the Capitol of Barbieland, with the return of the president and ‘democracy’ with extensive female representation. In other words, everything that history has already shown to be completely inadequate in ending women’s oppression is presented as a solution, and the path to this is the individual awareness of each Barbie through feminist consciousness, while provoking fights and jealousy among their respective partners, Ken. Thus, even when they address the issue of fighting for rights, they do so in a bourgeois manner, reinforcing their own prejudices against women as manipulators.

With all of this in mind, it’s no surprise that the way society is organized at the end of the film, after all the talk about gender equality and gender roles, is nothing more than a repetition of the same way it was organized at the beginning of the film, with some insignificant changes. The roles that genders play in society remain unchanged, and women continue to perpetuate all the bourgeois stereotypes of appearance and behavior, but in a matriarchal society once again.

The movie makes it very clear that any criticism attempting to analyze the problem of women’s oppression without taking as a starting point the private ownership of the means of production and the class struggle cannot go beyond the simple defense of the most reactionary aspects of society. The bourgeoisie, represented in the film by the directors of Mattel, is nothing more than a comical antagonist who, upon realizing that their profits are not threatened by all the fine talk about “normal Barbies,” ends the film as yet another ally. The conclusion for them is: if we can profit from feminist Barbies, let’s create a variety of models. That is, “we’ll be feminists” if we can make a profit from it. The film makes it very clear: imperialism can accept the differences labeled as ‘diversity,’ incorporate them, and profit from them, as long as they do not threaten the foundations of capitalism. Diversity and criticism are welcome, as they can always serve to create new needs and fetishes for commodities.

Meanwhile, in the real world, where the vast majority of working masses survive, beyond the movie screens, there is no glamour, but the brutal exploitation of billions of women and men who work in precarious conditions, for example, in Mattel factories in Asia, which have been accused of violating basic labor rights.1

Perhaps the only usefulness of this film is to blatantly show that in the fight against female oppression, very different from what bourgeois feminists advocate, not all criticism is valid; on the contrary, it can be incorporated and serve as support for the entire old order.

The Great Socialist October Revolution in Russia in 1917 had already provided a strong practical critique of capitalism and patriarchy, and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China further deepened it. We must realize that we are lagging behind, and what is necessary is to take this critique to its ultimate consequences, waging a war against all exploitation and oppression that burdens the working class and especially women workers.

Declare war on bourgeois feminism, which, with its defense of “representation” as the main weapon in the fight for women’s “liberation,” is nothing more than a reformist deception easily assimilated by the capitalist system, which even profits more from it, since “empowerment” for these people is often synonymous with consumption.

For imperialist monopolistic capital, it doesn’t matter what the physical appearance of the dolls will be, as long as it brings them profit. In this regard, once again, bourgeois feminism is imbued with reactionary idealism, advocating that merely changing cultural representations is enough to change reality, and it serves as an auxiliary line in the maintenance of oppression.

When attempting to reinvent the doll, the new Barbie movie is nothing more than another product and another tool in the political and ideological struggle between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The bourgeoisie seeks to turn the criticisms that exist against the very system of oppression and exploitation it produces into another commodity from which it can profit. Criticisms of Barbie’s historical role as a representative of an unattainable standard of femininity, of companies that profit from a false notion of diversity, etc., are sterilized and become just another product consumed eagerly by opportunists who believe it’s progress, that any criticism is valid, and that the “reform” of Barbie is another step towards equality. We give no credit to this work. We don’t want to reform Barbie or this corrupt system of oppression and exploitation from which she stems; we want to overthrow it all. For that, what is needed is a single, strong critique and action against imperialism, reaction, and bourgeois feminism.